February

May

August

October

November

December

- US Diver Don Harper: Melbourne Olympics Silver Medalist and Innovative Technician Passes Away at 85

- Legendary American Competitive Shooter Lones Wigger Passes Away at 80

February

May

August

October

November

December

Syd Hoare, a member of Team Great Britain’s judo team in 1964, the year judo debuted as an Olympic sport in Tokyo, died on September 12, 2017. While I never had the honor to interview him, I did read his wonderful book, “A Slow Boat to Yokohama – A Judo Odyssey.”

Based on his life story as a young judoka, “A Slow Boat to Yokohama” tells well his journey to Japan to learn at the mecca of Judo in the early 1960s, and then competing at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. I have borrowed those stories for a few of my blog posts:

For a wonderful look at Hoare’s past, here is an obituary penned by his daughter, Sasha Hoare, in The Guardian.

My father, Syd Hoare, who has died aged 78, was an Olympic judo competitor, author and commentator.

The son of Alfred Hoare, an executive officer at the Ministry of Defence, and Petrone (nee Gerveliute), a waitress, Syd enjoyed a wild childhood in postwar London: scrumping, climbing trees, jumping out of bombed-out houses on to piles of sand and being chased by park keepers. At 14, while a pupil at Alperton secondary modern school, Wembley, he wandered into WH Smith and found a book on jujitsu, which led to judo lessons at the Budokwai club in Kensington and sparked a lifelong passion for the sport.

Syd quickly became obsessed with judo and underwent intense training, often running the seven miles back to his home in Wembley to lift weights after a two-hour session at the Budokwai. In 1955, at 16 he was the youngest Briton to obtain a black belt and two years later won a place in the British judo team. He respected not only judo’s physical and mental aspects but its link to eastern philosophy.

For more, click here.

I have searched far and wide for books in English about the 1964 Olympics, and have built a good collection of books by Olympians who competed in the Tokyo Olympiad.

My conclusion? Runners like to write! Of the 15 books written by ’64 Olympians I have purchased, 8 are by sprinting and distance track legends. But judoka and swimmers also applied their competitive focus to writing.

So if you are looking for inspiration in the words of the Olympians from the XVIII Olympiad, here is the ultimate reading list (in alphabetical order):

All Together – The Formidable Journey to the Gold with the 1964 Olympic Crew, is the story of the Vesper Eight crew from America that beat expectations and won gold as night fell at the Toda Rowing course, under the glare of rockets launched to light the course. The story of the famed Philadelphia-based club and its rowers, Vesper Boat Club, is told intimately and in great detail by a member of that gold-medal winning team, William Stowe.

The Amendment Killer, is the sole novel in this list, a political thriller by Ron Barak, to be published in November of 2017. Barak was a member of the American men’s gymnastics team, who parlayed a law degree into a successful consulting business, as well as a side career as budding novelist.

A Slow Boat to Yokohama – A Judo Odyssey, is a narrative of the life of British judoka, Syd Hoare, culminating in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics when judo debuted as an Olympic sport. Hoare provides a mini-history of British judo leading up to the Olympics, as well as fascinating insight into life in Japan in the early 1960s.

Below the Surface – The Confessions of an Olympic Champion, is a rollicking narrative of a freewheeling freestyle champion, Dawn Fraser (with Harry Gordon), Below the Surface tells of Fraser’s triumphs in Melbourne, Rome and Tokyo and her incredible run of three consecutive 100-meter freestyle swimming Olympic championships. She reveals all, talking about her run ins with Australian authorities, and more famously, her run in with Japanese authorities over an alleged flag theft.

Deep Water, is an autobiography of the most decorated athlete of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Don Schollander, who won four gold medals as the most dominant member of the dominant US men’s swimming team. Co-written with Duke Savage, Schollander writes intelligently of his craft, the technique and the psychological, finding a way for a swimmer strong in the middle distances, to sneak into victory in the 100-meter sprint.

Escape from Manchuria, is a mindblowing story by American judoka, Paul Maruyama, whose father was at the heart of one of Japan’s incredible rescues stories – the repatriation of over one million Japanese nationals who were stuck in China at the end of World War II.

Expression of Hope: The Mel Pender Story tells the story of how Melvin Pender was discovered at the relatively late age of 25 in Okinawa, while serving in the US Army. Written by Dr Melvin Pender and his wife, Debbie Pender, Expression of Hope, is a story of disappointment in Tokyo, victory in Mexico City, and optimism, always.

Golden Girl is by one of Australia’s greatest track stars, Betty Cuthbert, whose life path from track prodigy in Melbourne, to washed-up and injured in Rome, to unexpected triumph in Tokyo is told compellingly in her autobiography.

See the remaining book list in my next post, Part 2.

It was October, 1964, the Olympics were in Tokyo, and the Japanese were expected to sweep their home-grown martial art. And in fact, Japanese took gold in three of the four weight-classes at the Tokyo Olympics.

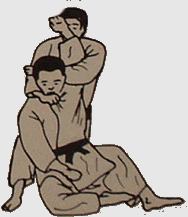

American James Bregman won the bronze medal in the middle-weight class at the inaugural judo competition at the Olympic Games. His accomplishment was the result of years of training, as well as a dedication to mastering technique or “waza“, and being the best judoka he could possibly be. But it was never about winning a medal.

Bregman, like a handful of other determined foreign judoka in Japan, trained with members of Meiji University, the dominant judo power in the 1960s. Training at Meiji was what you might find in a judo dictionary as meaning “glutton for punishment”. But Bregman trained, learned, and was proud to become proficient enough to earn the respect of his Meiji comrades. “My sempai was the captain of the Meiji University team. And when he put his hand on my shoulder and called me a “waza-shi” (a technician), that meant more to me than a medal.”

Bregman remembers judo in Japan as being a meritocracy, where attitude, grace and technique were the measures of a person. He said that twice a year, there would be public and open competitions called “koh-haku shiai“, where any judoka could come and compete. They would line you up in terms of your level, from the beginners’ level of “sho-dan“, then to “ni-dan“, “san-dan“, and upwards. You could have a line of hundreds of judoka, and the process is the first person in line gets on the mat with the next judoka and has a go. Whoever wins, stays on the mat to take on the next guy, and the next guy. Sometimes, a person from a lower rank takes on a person from the next rank up and wins a match or two. But very often, judoka are in the right rank, getting that feedback real time in front of all to see.

Bregman told me that when he first started attending koh-haku shiai as a ni-dan, “you’re basically a flying machine” getting tossed all over the place. But as you train, you get better, and over time, you’re throwing people, and eventually beating people above you in rank. “It’s a real learning experience,” Bregman told me, “putting to test all the things you learned from your training.”

One of his most impactful teachers was Bregman’s sempai, a judoka named Seki who was a year ahead of Bregman. He said he trained every day with Seki, who was third or fourth best in the middleweight class in Japan, learning the right way to stand, mat work, choke techniques, and mat presence, lessons that served him well in the Olympics. Bregman explained that Seki would train Bregman about mat presence by practicing near the “joh-seki“, a wooden floor where shrines were placed for special occasions. Since the joh-seki was hard, falling on it was something Bregman wanted to avoid.

It was hard enough thrown on the tatami, which are not exactly cushions. Even though we know how to fall, it hurts. What he was teaching me is that you have to be conscious of where the edges are, to have total mat awareness. You need to know where your opponent is going, and where you want to go. Most of us were taught to fight in the middle of the mat. This was due to the early rules of judo. If you go to the mat, and you stepped out, they brought you back after stopping the match, so throwing a person outside the mat was, in a way, wasted effort. So Seki taught me how to anticipate the other person’s move and maneuver him to where you want to go.

At the Tokyo Olympics, Bregman faced off against a judoka from Argentina named Rodolfo Perez. In the video, you can see Bregman pick up Perez’s right leg, putting him off balance. But Bregman notices that he is just about to push Perez off the mat, which would have stopped the match and resulted in no points. Noting where he wanted to go, Bregman planted his right foot at the edge of the mat, and while still holding Perez’s leg suspended, he turned the two of them nearly 180 degrees so that Bregman was facing the middle of the mat. Then with his left leg sweeping from behind, he tripped up Perez in a kosotogake. Perez fell safely in bounds and Bregman moved on to the semi-finals.

Judoka James Bregman Part 2: The Stoic Professionalism of Judo

My focus in this post is primarily on Japan, so get your Japanese cultural lessons here:

A friend from England met him at the port, and drove him into Tokyo. That evening he had soba for dinner, and fell into a sleep so deep he didn’t feel an earthquake that rumbled in the middle of the night. In his first full day in Japan, he opened up a bank account, visited the legendary home of judo, the Kodokan, and then bought his judo wear, called judo-gi.

On Day two in Japan, Hoare had his initiation to Japanese judo. He picked up his brand-new judo-gi and made his way back to the Kodokan. He bumped into fellow Brit and judoka, George Kerr, who helped Hoare navigate in his new judo world. Hoare watched George and another friend John, walking where they walked, bowing when they bowed. And when he entered the main dojo, as he explains in his wonderful autobiography, A Slow Boat to Yokohama, Hoare was impressed.

On Day two in Japan, Hoare had his initiation to Japanese judo. He picked up his brand-new judo-gi and made his way back to the Kodokan. He bumped into fellow Brit and judoka, George Kerr, who helped Hoare navigate in his new judo world. Hoare watched George and another friend John, walking where they walked, bowing when they bowed. And when he entered the main dojo, as he explains in his wonderful autobiography, A Slow Boat to Yokohama, Hoare was impressed.

I had never seen so many black belts in one place before. All were standing to one side, waiting for the mass bow to the teachers. In one corner on a wooden stand stood a massive barrel-shaped drum. An old grey- headed sensei approached it and hammered out a tattoo of about fifteen beats which quickly got faster, followed by two slow bangs at the end. Then on the command “seiza!”we all moved forward and knelt down in orderly ranks. Next followed “Ki o tsuke! Sensei ni rei!” and we all lowered our hands and head to the mat.

Hoare of course trusted Kerr to guide him in the right way in his first few days in Japan. After all, he was literally fresh off the boat. Kerr said that Hoare could go up to anyone on the floor and ask for a tussle, called a “randori”. Kerr pointed out a “fairly chunky Japanese” standing near them, and suggested that Hoare ask for a randori. Hoare didn’t think too much about it and did as was suggested.

At that time I had done virtually nothing in the way of judo or any other kind of training for nearly two months, and it felt a bit weird to be back on the mat. After about three minutes when nothing much had happened, we stumbled to the ground and I got him in an immobilization hold called kuzure-kesagatame. I think, he wasn’t trying too hard and let it happen. I kept him under control for about twenty seconds (a thirty second hold-down would have been a loss) during which time his struggles got rougher and rougher.

The hold-down was one I had worked on quite a lot in the UK and was deceptively strong. He broke out of the hold just before time, and when we stood up again he began pasting me from one end of the hall to the other. I took a hammering and endured it for about ten minutes, then said “mairimashita” and bowed off. I staggered back to George and asked him who he was. “Oh”, he said most innocently, “that was Inokuma, the current All-Japan champion.”

Isao Inokuma, who took gold as a heavyweight at the 1964 Olympics, was at that time actually the runner up in the 1960 and 1961 All-Japan Championships, but became All-Japan champion in 1963. At any rate, Inokuma was a judo legend, and Hoare’s painful introduction to judo in Japan.

Training in the martial arts can be brutal. Olympian Syd Hoare felt this keenly when he moved from his home country of England to Japan to study judo with the very best. Wrenched knees, broken noses, dislocated shoulders, ripped-off toe nails – doesn’t matter. Stay calm, and carry on.

Training in the martial arts can be brutal. Olympian Syd Hoare felt this keenly when he moved from his home country of England to Japan to study judo with the very best. Wrenched knees, broken noses, dislocated shoulders, ripped-off toe nails – doesn’t matter. Stay calm, and carry on.

One of the more notorious training routines of judo (back in the day) was to purposely strangle someone to unconsciousness. This was partly done to teach the judoka how to revive the unconscious. It was also done to educate (to not get oneself in a position to be strangled, I suppose).

Hoare, who represented Great Britain at the 1964 Summer Games, wrote in his wonderful book, “A Slow Boat to Yokohama”, how his training in England included the “kata-hajime” strangle technique. Here is a somewhat chilling description.

Hoare, who represented Great Britain at the 1964 Summer Games, wrote in his wonderful book, “A Slow Boat to Yokohama”, how his training in England included the “kata-hajime” strangle technique. Here is a somewhat chilling description.

“Then it was my turn to strangle my partner out but he was one of the fighters. Even as I was putting my hands in place for the kata-hajime strangle, he tensed his neck, preventing me from taking the full position. So, I softly started again, and then locked it on hard and quickly. Immediately he grabbed my hands and tried to tear them away from his throat, but the strangle was on securely. He began to flail around gagging and choking. At one point he arched violently

You must be logged in to post a comment.