Are the Olympics a worthy investment? Does the investment create legacies for the host country?

The answer to those questions are often “no”, unfortunately, at least in terms of the billions spent on structures like stadiums and other various sports venues.

Many of the structures built for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics still exist, like the Nippon Budokan, the National Gymnasium and Annex, as well as the Komazawa Olympic Park venues. Not only that, they live and breathe. Click below on the video to see and hear what I did.

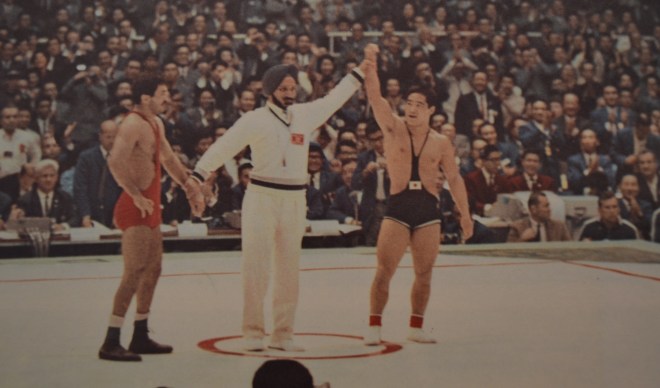

On Sunday, May 1, during the long break in Japan known as Golden Week, I took a short bicycle ride to Komazawa Olympic Park, and walk where 1964 Olympians walked. The Park is a collection of venues: Komazawa Gymnasium where Japan won 5 of 16 total gold medals just in wrestling, Komazawa Hockey Field where India beat Pakistan in a memorable finals between two field hockey blood rivals, Komazawa Stadium where soccer preliminary matches were played, and Komazawa Volleyball Courts where Japan’s famed women’s volleyball team mowed through the competition until they won gold at a different venue.

On that day, thousands of people were enjoying unseasonably warm weather under clear, blue skies. The tracks around the park were filled with runners. The gymnasium was hosting a local table tennis tournament, and the stadium was prepping for the third day of the four-day Tokyo U-14 International Youth Football Tournament.

In the plaza between the various Komazawa venues, hundreds were enjoying the weather with great food and drink. I was pleasantly surprised to find draft Seattle Pike IPA. While enjoying the cold beer on the hot day, surrounded by hundreds of people loving the day, I realized that Japan in the 1960s made great decisions in planning for the 1964 Olympics. I had a similar revelation earlier when I visited the National Gymnasium months earlier. So much of what was built for those Summer Games are a part of the everyday life of the Japanese.

Japan built a fantastic legacy for 1964. What legacy will Japan begin in 2020?

You must be logged in to post a comment.